|

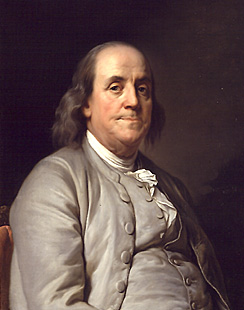

| Portrait of Benjamin Franklin, circa 1785, by Joseph-Siffrein Duplessis, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Washinton |

Franklin was born January 17, 1706 to Josiah Franklin and his second wife Abiah Folger, Puritans living in Boston, Massachusetts. Franklin ran away to Philadelphia, PA at the ripe young age of 17, working in various printing shops. By 1727 at the age of 21, Franklin had formed the Junto as a place to discuss morals, policics, and natural philosophy. In 1736, he created the Union Fire Company as Philadelphia's first volunteer firefighting company.

Fast forwarding many years and many accomplishments (The Pennsylvania Gazette, Library Company of Philadelphia, American Philosophical Society, Justice of the Peace for Philadelphia, etc.), Ben Franklin found himself in London in 1765 arguing on behalf of the Colonies against the Stamp Act. His testimony eventually led to the repeal of the Act, and resulted in Franklin becoming a leading spokesman for the Colonies.

On May 5, 1775, Franklin returned after his second mission to England, with the fighting between the Colonies and the British already begun (the Battles of Lexington and Concord began on April 19, 1775). The Pennsylvania Assembly unanimously nominated Franklin to the Second Continental Congress, and in June 1776 he was appointed to the Committee of Five to draft the Declaration of Independence.

Franklin served as the first United States Postmaster General, was ambassador to France from 1776-1785, served as the sixth president of the Supreme Executive Council of Philadelphia (fancy speak for governor), and late in life was a leading figure for the abolition of slavery in America.

Benjamin Franklin died at his home on April 17, 1790, age 84, after leading an eventful and important life for early America. Today, he is still remembered on the $100 bill, as the name of numerous warships, and towns throughout America. Another interesting fact was that he bequeathed 1,000 pounds ($4,400, or approximately $112,000 in 2011) to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia to appreciate for 200 years before being spent. Through that miracle called compounding interest, more than $2,000,000 had accumulated in the Philadelphia Trust and $5,000,000 in the Boston Trust by 1990. Philadelphia ultimately spent its money on scholarships for local high school students, and Boston used it to establish the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology.

Benjamin Franklin and Mead

For those readers left wondering why on a blog dedicated to mead and its production I would devote this time to Benjamin Franklin (other than the semi-obvious, it's Presidents Day and we need make mention), here is some more wonderful trivia for you. On 19 December, 1789, Benjamin Franklin wrote:

Dear Friend: -- I have received your kind Letter on the 5th Inst., together with your present of Metheglin, of which I have already drank almost a Bottle. I find it excellent; please to accept my thankful Acknowledgements.'Tis a shame little is known of who this letter was addressed to, or the underlying recipe in reference. But here's to an influential man in early America, a Founding Father, and for those in the know, a lover of mead!